The following interview and article was posted by PERF’s Executive Director, Chuck Wexler, on February 1, 2025. Congratulations to our 1st Vice-President, Terri Tobin, on her retirement and lifetime of achievements!

Link to article: https://www.policeforum.org/trending1feb25

PERF members,

Terri Tobin joined the New York Police Department in 1983. In 2019, she was promoted to assistant chief, a rank attained by only three other females on the job at the time. Tobin retired as Chief of Interagency Operations this past December.

Born into a police family, Tobin earned a Ph.D. and master’s degree in criminal justice, a master’s in social work, and a bachelor’s in sociology/social work. She is also a certified social worker.

During the 9/11 attacks, Tobin arrived on scene just as the Second Tower of the World Trade Center was struck. She was seriously injured while rescuing survivors from the wreckage and would go on to receive the NYPD’s Medal of Valor and Special Congressional Recognition for her brave actions on that day.

Here is our conversation.

Chuck Wexler: Tell me a little bit about your family, because it feels like you’ve had a police family all your life.

Terri Tobin: My dad was an NYPD officer. My mother had two brothers. One was an NYPD sergeant, and the other was a Maryknoll missionary priest. I’m the youngest of five, and four out of the five of us followed my father’s footsteps into law enforcement. The joke in my family is he let my sister off the hook because she married a cop.

My father was actually the best advertisement for the NYPD. He sold the job. He didn’t speak about it, but you just knew it was fun. It was engaging.

I grew up when they had a police camp in New York. We would go away to police camp for summer vacation. We knew so many police families. There was so much camaraderie, and you just got the impression that people were really fulfilled in doing what they were doing.

I actually didn’t plan on joining the NYPD. I had taken the [recruitment] test because we had a bet among my siblings about who would do the best. I continued to go along in the process, and it happened to come along just as I was graduating from college. My father said, “You’ve been in school for four straight years. Why don’t you just continue going to school? I think you’re really going to enjoy this.” And he was right.

Terri Tobin. Source: NYPD

Wexler: Now, it’s 1983, and you’re a young woman joining the NYPD. What was it like joining the NYPD at that time?

Tobin: Well, there were really so few of us in the early 80s. When I came on, women were less than 4 or 5 percent of the entire workforce.

Wexler: Was it at all challenging? Or did they just accept you?

Tobin: I’ll give you an example. I think it was in ‘85 or ‘86, and I was going to my first “women in policing” conference at the same academy I had gone through, on 20th Street in Manhattan. The speaker, who was from another city agency, had been picked up [in a car], and she said to the man who brought her, “I would like to run into the restroom before we go into the auditorium.”

She walked into the bathroom, and there were urinals. So, she quickly turned around and came out and said, “I’m sorry. I walked into the men’s room. Could you tell me where the ladies’ room is?”

And the man said, “Oh, no, that’s the ladies’ room.”

That was something we didn’t give a second thought about, right? But when the guest speaker got on stage, her point was that when institutions do things like not removing urinals, that’s the way an institution tells people, “We don’t really think you’re staying.”

I have to tell you, by the time we left that building, all the urinals were boxed up in every ladies’ room on every single floor.

Wexler: It feels like you’ve had a different kind of career. You have a master’s degree in social work. You had a bachelor’s in sociology, and you would wind up getting a PhD. It feels like you’re kind of unusual in that respect.

Tobin: The NYPD has a lot of joint ventures with universities and colleges, and they offered lots of scholarships. I put in for one to get my master’s in criminal justice, and they asked me to stay on for the Ph.D. at SUNY Albany.

I just said yes to every opportunity that was there. Someone would say, “Hey, are you interested in this? You should apply for this.” Whether it was for education, a new unit that was forming, a different unit than where I worked, I’d take it.

That’s what makes policing so interesting — the amount of opportunities that are available to people.

Wexler: You were the commanding officer of the Behavioral Health Division. What was that like? What were your responsibilities in that arena?

Tobin: Most of the time, police are the first responders to 911 calls, and a significant number of calls that we were receiving had to do with people in a mental health crisis. We decided to form a division, with several subunits underneath it, that put the best tools in the officers’ toolkits to respond to these calls.

We know that we’re not the best city agency to respond if a health-centered response is called for. But if we are the first responders, let’s give officers the best tools to deal with people who are in crisis, and then do the warm handoff to whatever city agency is responsible for actually helping them navigate the system.

Wexler: I know this may be difficult to talk about, but 9/11 was a defining moment in your life. You received the NYPD Medal of Valor and a Special Congressional Recognition. Would you be willing to talk about what happened, and what your role was that day?

Tobin: I was one of many, many NYPD first responders, and I would say the same of the FDNY, Port Authority, EMS, and all our first responder community. It was amazing to see the professionalism with which we responded on 9/11.

I was a lieutenant assigned to the press office at that time. My boss called as soon as we knew that the first plane had hit, and he said he wanted a lieutenant at the scene. I responded with a sergeant and got there quickly enough that we were present when the second plane collided.

To be honest, when we were responding, we did not know it was a commercial airline that had flown in[to the building]. So, I was not prepared for what I saw when I got there.

We were there to get the press together, but really what everyone needed to do was just be first responders and evacuate people as much as possible. We went into that mode.

At one point I crossed paths with Joe Dunne, who was the first deputy commissioner. He said to me, “Terri, there’s a report of a third plane in the area. Get on the ESU [Emergency Service Unit] truck and get a Kevlar helmet.” I have to tell you, his order to get the helmet wound up being so crucial, because it saved my life.

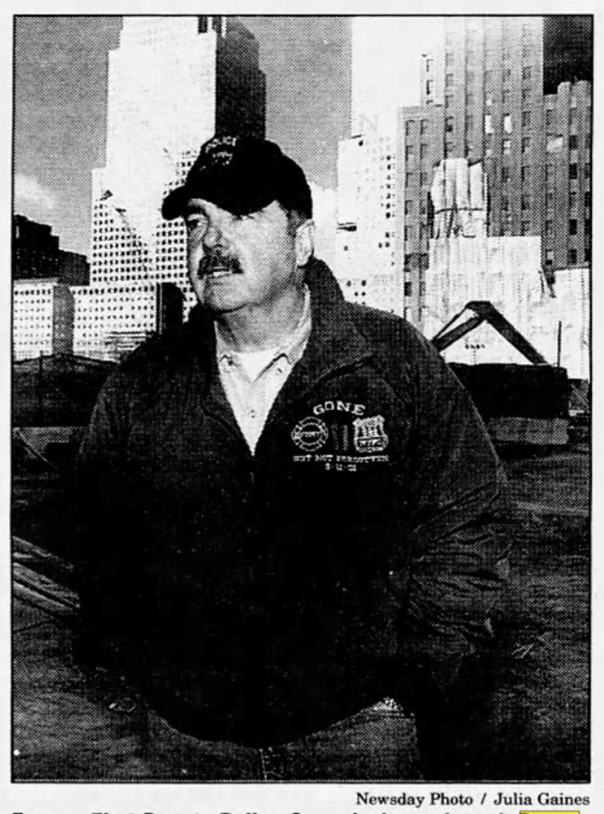

Joe Dunne, former NYPD first deputy commissioner Source: Newsday, archival

We were evacuating people, and I was escorting a photographer out of the building when the South Tower came pancaking down. The force of that explosion blew me across the street.

When the building came down, a piece of cement with rebar in it went right through that Kevlar helmet, split it in half, and a piece of cement and rebar got embedded in my skull. It had to be surgically removed later in the day.

Terri Tobin shortly after the 9/11 attacks. Source: NYPD

By the grace of God, there was a firefighter who found me after I had been buried in a pile of rubble up to my chest. He saw me and shouted instructions for what to do. The firefighter was able to extricate me from the pile. Then he, another person, and I were able to dig a couple of people out from the pile and from underneath their vehicles. And no sooner had we gotten someone out, than people were running toward us, telling us that the second tower was coming down.

Without a helmet, I felt very vulnerable, so I was going to try to make it to the river. Of course, I thought I was running like Carl Lewis. I didn’t realize I had a broken ankle. I wasn’t going to make it to the river, and I got smacked in the back by something. I was able to get up, and I ran into the nearest apartment building. All the lights were down, and smoke started coming through the elevator shaft. At this point, to be honest with you, I thought every building in Manhattan was going to collapse.

Once the smoke started to come through the elevator shaft, I made my way to the stairwell, because that’s what we’re taught. I opened up the stairwell, and there were all these people lined all the way up the stairwell.

As the smoke began to diminish, I was able to connect with people from our Technical [Assistance Response] Unit. We started evacuating people toward the docks, where they were moving people by boat to either Staten Island or New Jersey.

At one point, a detective said to me, “Are you feeling alright?”

I said I was fine, but then I noticed I had something sticking out of my back. Apparently when I had gotten whacked on the back, that was when a piece of glass went in between my shoulder blades and embedded itself.

The detective had EMS training and recommended we leave the glass shard in place since we might cause more damage by removing it. Once we got the people set in the right direction, and we saw the boats coming into the harbor, he helped me down to get on a boat over to Ellis Island, which is where they were taking people to evacuate to local hospitals.

It just was an unbelievable experience, and by the grace of God, I lived. But the response by NYPD, NYFD, EMS, and the Port Authority was just unbelievable. We’ve lost well over 400 people working on the pile since that day to 9/11 health-related issues. It’s so devastating because those deaths have been really hard on people. But I think if you asked anyone, they wouldn’t change what they did on that day.

And every September 11th, I make sure I connect with Joe Dunne to thank him, because it weighs very heavily on him that we lost people on 9/11. And I always want to remind him that he saved my life that day, and here we are, 24 years later.

Wexler: I suspect you could have retired after that if you wanted to. But you came back to work. That, by itself, says a lot about you.

Tobin: I think, truly, I was meant to be doing what I was doing on 9/11. It made me even more committed to public service and the role that the NYPD plays every single day.

Wexler: The NYPD is so much a part of your DNA and so much a part of who you are. How has it been adjusting to your retirement?

Tobin: Well, it’s only been a month. I am doing contracting work for HIDTA, which is the High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area program. I’m continuing to do some of the projects that I had done with HIDTA in my role in the NYPD, working with New York/New Jersey HIDTA Director Chauncey Parker on our drug overdose response and gun violence reduction strategies.

Terri Tobin during her final walkout retirement celebration.

Wexler: Last question: Policing is facing a significant hiring challenge. What would you say to police chiefs about how they should go about attracting the next generation of police officers?

Tobin: I think one thing police chiefs nationwide can say is that you’re never going to have a regret that you entered the profession of policing. Because it’s such a public service, and you get as much out of it as you put in.

It is absolutely one of the most remarkable careers that someone can choose. I also think that the profession has done a good job adjusting to what the next generation is interested in. I see lots of efforts being made toward health and wellness, and making sure resources are there, because of all the trauma that police professionals respond to every single day. So, I think the adjustments are there. I just don’t think we do as good a job selling what we do to the public and to new recruits as we could.

A major thanks to Terri for taking the time to speak with me. We at PERF want to congratulate Terri on an incredible career and we look forward to seeing how she makes a difference next.

Have a great weekend!

Best,

Chuck